Throughout 2023, this publication featured Northeast Minneapolis Arts District artists who are focused on the environment in their art practice. Each in their own way is probing our human relationship with the rest of the natural world. Each is considering the unique power art can hold in calling our collective attention to an environmentalist cause.

Among the artists featured, there is a huge range in their approach to these questions. Some tackle climate change directly by using their art to convey a message through their subject matter. Others investigate the environmental impact of their own artmaking materials, reusing and upcycling found objects and waste product or using handmade dyes from foraged plants.

Annie Irene Hejny is one artist whose work evolved in 2023 from being primarily inspired by water to being a direct tool of freshwater protection. This year, Hejny embarked on a training program to become a Minnesota Water Steward with the Mississippi Watershed Management Organization (MWMO) and Freshwater. Her focus was an overlooked winter water polluter: road salts. A single teaspoon of road salt, Hejny learned, is enough to pollute five gallons of freshwater forever. Furthermore, a University of Minnesota study found that 78% of salt applied in the Twin Cities for winter maintenance ends up in groundwater or local lakes and wetlands. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency estimates that fifty Minnesota lakes and streams now have chloride levels above the standard designed to protect fish and other aquatic life.

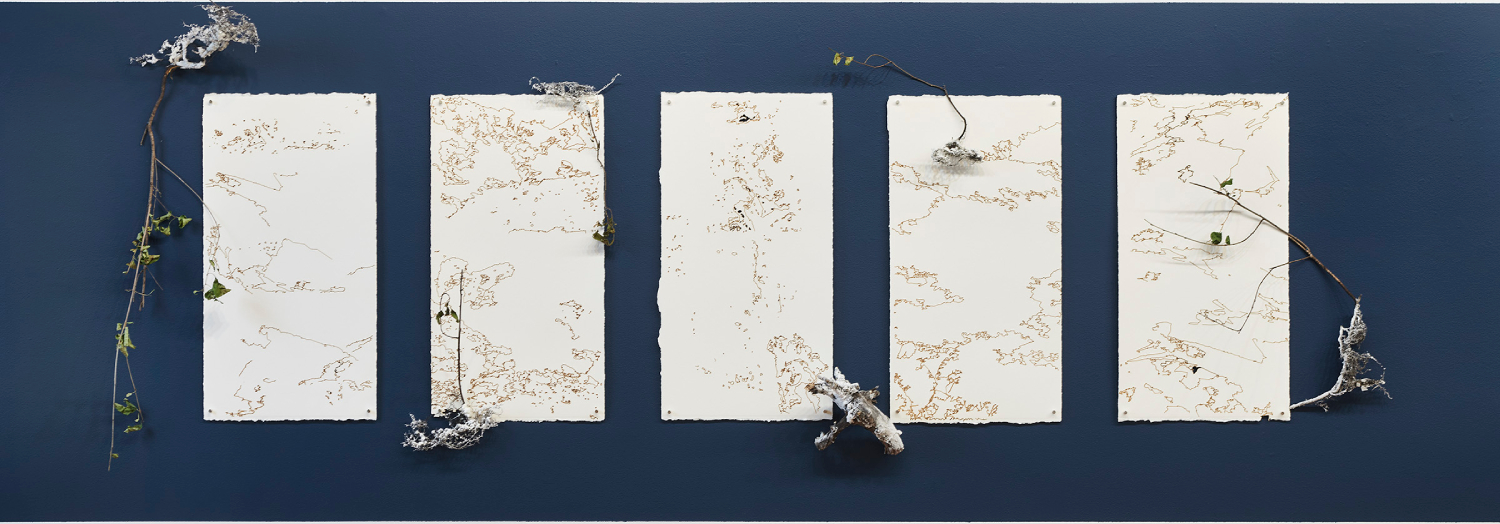

Hejny’s capstone project, called “Seeing Salt,” was the first time she had used her art as a direct messaging tool. For many years, she has developed a process of using collected water and sediment from beloved bodies of water in her abstract acrylic paintings; in “Seeing Salt,” she iterated on that process to incorporate collected road salt, illustrating its corrosive impact on other materials and emphasizing that the materials will continue to erode. She debuted the work during Fall Open Studios, hosting an informational panel on the harm of road salt and answering questions about safer use. One piece showed granules of salt dispersed at 3” intervals, demonstrating its correct application.

Hejny said that training to become a water steward felt like “a natural evolution” for her process, in part because it equipped her with knowledge and tools for much more direct community engagement. Many visitors to her studio told her they had no idea salt was a pollutant, some because they thought of it as a natural material, others because it dissolves to become invisible. Hejny, through her artworks, made the effects visible.

But community engagement must also come with empathy, Hejny observed. Environmentalist calls to action are almost inherently confrontational; they usually include an indictment of some aspect of the way we all live. No matter how informed or well-intentioned the individual, modern society is tilted in ways that incentivize lifestyle choices that threaten the long-term health of the planet. The environmentalist often finds themselves trying to promote a behavior that is harder, more expensive, or less accessible than many people can adopt. And no one wants to be lectured.

According to the artists we interviewed this year, this is exactly where art finds its unique place. Again and again, artists saw the ways their art created space for a conversation that would never have taken place otherwise. Fiber artist Deborah Foutch found that her depictions of soil horizons received a warm welcome among farmers, opening conversations about soil health and farming practices that would otherwise have been closed to her. Claudia Poser recalled how people recognized their favorite trees in her “Vanishing Species” series, giving opportunity to call attention to plant life’s vital and threatened role in our own survival as a species.

None of the artists we interviewed this year is trying to sugar coat the dire realities of climate change. Brooke Bartholomew’s paintings in “Two Degrees Warmer” were vivid and unflinching in their characterization of the causes and effects of ecological destruction. But even at its most confrontational, it is as if the artwork creates a kind of buffer zone between artist and viewer, dispelling some of the natural awkwardness and allowing someone to process difficult information in privacy.

Some of this effect comes down to the physicality of art; people respond differently to physical beauty and form than they do to facts and figures alone. Art doesn’t only convey information, but emotion. Both Aaron Dysart and Marjorie Fedyszyn have used tree forms as embodiments of loss and grief, to powerful and moving effect.

For her part, Hejny frequently opens a conversation simply by asking people, “human to human,” about the water bodies they love—and most Minnesotans are ready with an answer. Ultimately, people are moved to action when they feel connected to the cause. Environmentalist art connects people to its cause not by telling people they are doing something wrong, but by embodying something people love.

Article by Katherine Boyce