Though we may not think of art and religion overlapping much now, there were whole centuries when art was made for primarily religious purposes, to convey mythologies and theologies, and to consecrate what was considered holy. Claudia Poser discovered this function of art as a child growing up in Germany; her mother loved art history, “so she dragged me to European churches every time we went on vacations.” On these visits, Poser saw countless reliquaries, enclosures to house the bones of saints, pieces of the cross, or other holy relics. They made an impression—but not the one originally intended. “I started thinking, that’s not what I think is important.” What’s truly sacred, she would come to realize, are seeds and legumes: “all of the things that make life possible.”

As a ceramicist in the Northrup King Building, Poser has referenced this historical context in several series of art about the environment. “I started building reliquaries out of clay.” Where traditional reliquaries were made with silver and gold, and encrusted with precious gemstones, Poser felt that clay, being earth related, was a better material for what she wanted to house; inside, she placed seeds.

In another series, Poser created wall pieces in the shapes of Gothic windows, inlaid with the silhouettes of endangered species. This included elephants and tigers, but also species much closer to home in Minnesota: bats, fish, and butterflies. The religious motifs she uses offer an implicit counterpoint to interpretations of Christianity, which have historically leaned toward a hierarchical relationship to the earth that favors humans.

All of this, for Poser, “began with the question of what’s holy. I was thinking about what was sacred to me.” In place of traditionally religious answers, Poser has found her sense of what matters in an environmental reality. “If all the green plants in the world were to disappear, we’d all be dead in three days. We wouldn’t have any oxygen. We just don’t think about that, that human life is completely dependent on seeds.”

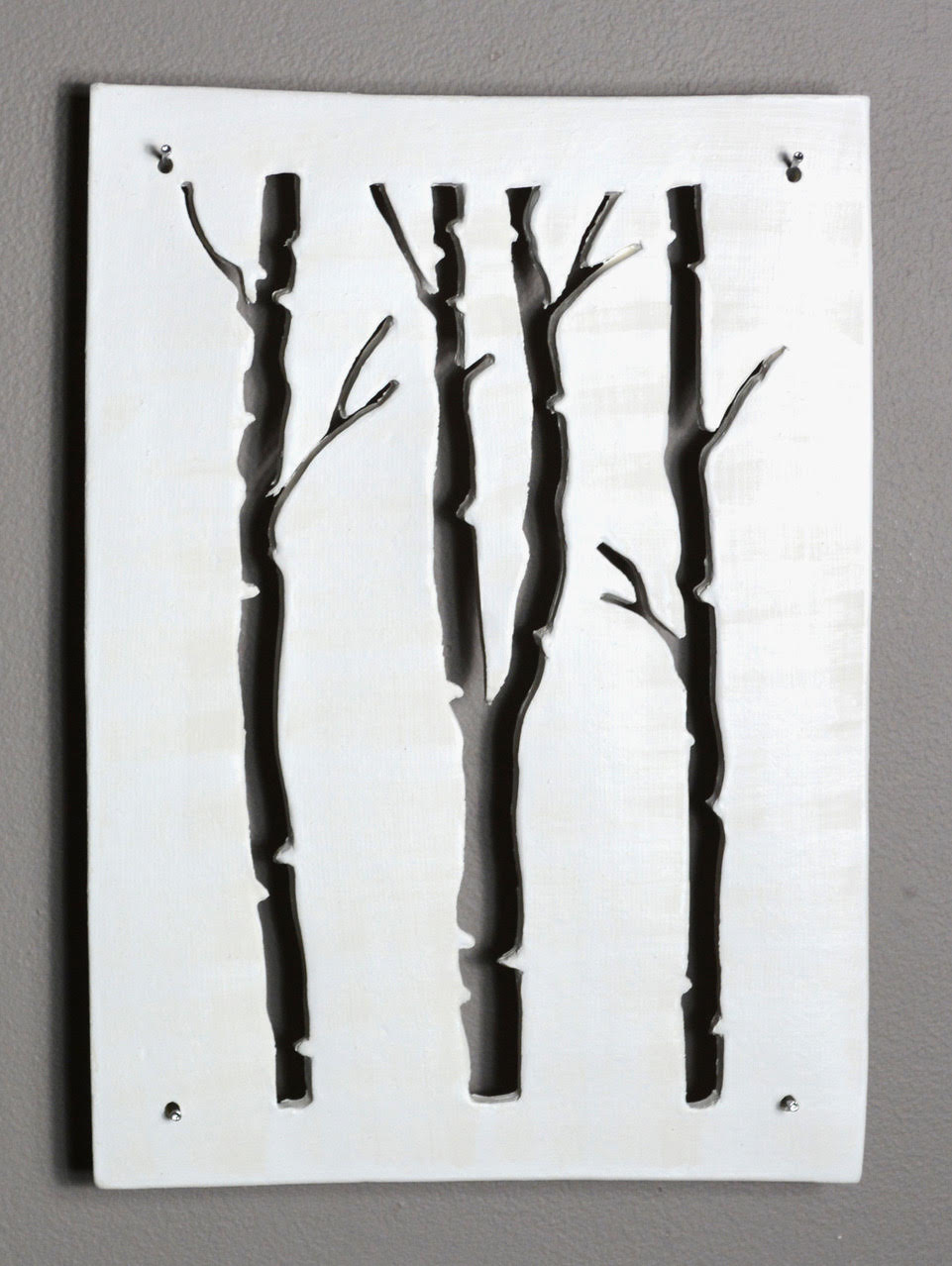

Poser has sought to spotlight the disappearances that are already happening. One case that has captured her concern is the threat posed by sulfide mining near the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA). Environmentalists have opposed leases to mine the copper and nickel deposits in this area because of the risk of releasing sulfuric acid into the watershed, and while one such project near Ely was halted by the Biden administration in January, others in northeastern Minnesota proceed. For a series called the Citizens of the BWCA, Poser researched the animal and tree species of the BWCA, “thinking about how to express how it would feel to lose them.” She cut their silhouettes out of clay tile pieces, the negative space expressing the absence of the trees and animals.

Most of Poser’s work is made of terra cotta, which she prefers because it requires a relatively low firing temperature. But for the BWCA trees and animals, Poser opted for a white paper clay. She said its more ghostly quality felt appropriate for work that was primarily about absence and loss. Reflecting on many of her works from this and other series like it, she said “each one of those pieces felt like a processing of grief.” These works, particularly her trees, have connected with others as well. She recalled one visitor who saw one of her pieces and started crying, and another who could identify every tree shape in her series.

While she has engaged in environmental activism, whether by joining demonstrations, attending hearings at the capitol, or donating money, Poser said art is the vocation that comes more naturally to her. “There is a constant feeling that you’re supposed to be out saving the world. Is making art about it enough or am I just indulging myself?” She said especially “coming from a northern European culture where the idea is that if you’re having fun, it can’t really be worth anything. We can’t all be Mother Teresa on behalf of whatever the cause is—but we all feel like we have to.”

It bears remembering that Mother Teresa didn’t save the world either. “One of the things that has been really helpful to me is thinking about everything as a community effort. We all have to do what we can do, contribute toward the things that matter to us, and if we all do that, then hopefully we can make some progress.” Ultimately, this is the hope Poser places in the art she is making. “If you can move just a few people, you’ve probably done what you need to do.”

Poser has devoted her work to venerating the earth, and in so doing, she moves people to consider it with more reverence than we are sometimes inclined to. “We can’t have life without venerating the earth,” she said. The latest piece she put up on her wall is called Lifeboats. In the many boat-shaped pieces mounted to the wall, she has placed the things she feels we need to rescue, the sacred things on which life depends: seeds.

— by Katherine Boyce