A conversation with St. Paul artist Ta-coumba T. Aiken is a lot like taking in one of his paintings: Many layers and winding threads lead to findings that might shift as you further consider them. There’s a playfulness that also can manifest itself in his work.

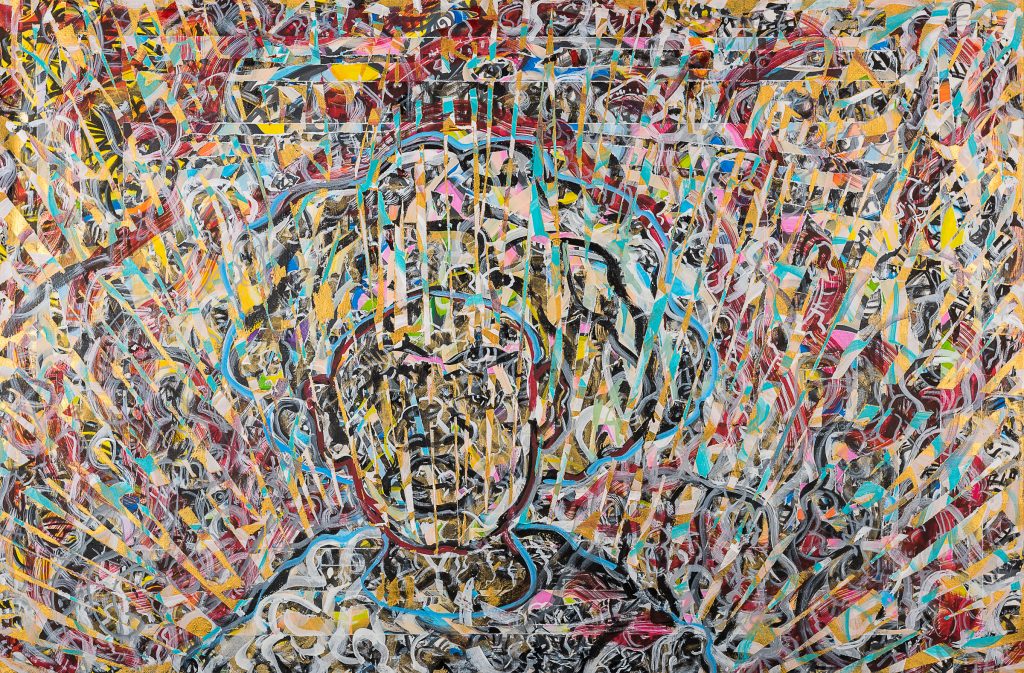

“It’s like a motion picture … or maybe an emotion picture,” he said, laughing at his play on words, but also dead serious as he described studio visitors’ shifting reactions to “Awakening,’’ the title piece in his upcoming solo exhibition at Northeast’s Dreamsong gallery.

He created “Awakening” and others that will be in the show, by using strips of tape to mask parts of the canvas as he applied color; multiple applications of tape and paint results in what Dreamsong co-owner and curator Rebecca Heidenberg calls “vortexes of color,” and in the case of Awakening, rays radiating outward.

Aiken compares “Awakening” to African drumming and Gregorian chants: “After a while you’re not hearing the repetitive, you’re hearing the tones that are going through the repetitive, the swirling of something else.” That visual swirling surrounds a figure looking out from the background of the painting. “You look through the shards and the beams of light and notice that you’re not going to get the same expression every time.”

Aiken, who last month added a Guggenheim Fellowship to his long list of grants, fellowships and awards, is an established artist in the Twin Cities whose public art appears in many venues, from the enameled metal of the exterior of Walker West Music Academy and 40-foot canvases that hung in a lobby at the McKnight Foundation. Some of his works are part of the collection at the Walker Art Center; the most recent a triptych “No Words,” that he completed in response to the murder of George Floyd and was displayed in the exhibition Five Ways In: Themes from the Collection.

Aiken flowed seamlessly between the present and past as he talked about his work and life as an artist. He evoked his mother’s gaze as he described how “No Words” evolved and how he was haunted in his live/work space by the woman depicted in the central panel. For a while, he said, he needed to remove the canvas from the studio.

“It was like, if I did something really bad … And I say, ‘Hi mom,’ and then I get ready to go wash my face and hands and to set the table. And she’s sitting there, staring at me … And then I start confessing everything that I’ve done in the past ten years. It’s that look of total disbelief. There’s no words, she has nothing she can say. It’s like disappointment with just a glimmer of hope in there.”

He said the Dreamsong exhibition is the first time that gallerists have sought him out, in spite of his being well known, and that led to his remembering what he said was his first exhibition at the age of 6, in his family’s home in Evanston, Ill. His mother was a house cleaner, his dad a garbageman; the train tracks were next to their backyard. They ran a religious household, very strict – as one might guess from the “No Words” musing – and they were supportive of his talent for art.

His mother was a healer, he said, and he took on her legacy when she died on his 20th birthday. “I inherited something that I didn’t want. But it has served me well, and I serve it well,” he says. His artist’s creed: “I create my art to heal the hearts and souls of people and their communities by evoking a positive spirit.” His “spirit writing,” as he calls his painting process, is a dialogue with community, something that he himself doesn’t always fully understand, with his creations seen differently by each person. “Do I trust between me and the creator, that they will see what they need to see, not what I want them to see?” he asked.

Also passed on from his parents, the importance of supporting community. He remembers being disciplined for taking out and thawing meat from the wrong freezer in the basement – from the one that was used to give food to neighbors who needed it – and being asked to turn his back when someone in need would show up at the door, so that he wouldn’t see who they were.

As Aiken reflected on his material needs and the extent to which his art has and hasn’t provided for them, he talked about how the sale of “No Words” to the anonymous donor who bought it for the Walker has allowed him to support other artists, funding no-strings-attached stipends to artists of color belonging to the ROHO Collective. It allowed him to buy more of other artists’ works, he explained, pointing to his collection on the wall behind him. Last year he also contributed to an arts and history program at the Minnesota African American Museum, which provided grants to Black emerging artists.

Aiken’s Dreamsong exhibition will be the sixth show that Heidenberg and her husband, Gregory Smith, have staged since they opened the gallery and cinema space at 1237 4th Street NE in June 2021. “We have been offering solo exhibitions and group exhibitions that focus on local artists, but in conversation with the broader contemporary art world,” Heidenberg said.

She said that she had been aware of and “pulled in” by Aiken’s work previously, but it was a summer art crawl last year that led to several studio visits and conversations resulting in the show named Awakening, which will feature recent paintings and collages on paper that incorporate the paint-covered tape used to create the paintings. The show will open May 13 with a reception from 5 – 7 p.m.

“Our plan is not only to present this incredible show at Dreamsong and publish an important accompanying catalog, but to ensure that Ta-coumba’s work receives critical attention and acclaim in the wider art world, within and beyond the Twin Cities,” Heidenberg said.

Garnering that exposure was one of Aiken’s goals in submitting a proposal for the Guggenheim. “You have got to be pretty arrogant’’ – he corrected himself: “Or pretty confident- to say I’m good enough, just people don’t know it. So let me get out there, and I can guarantee you, I will work with the same vigor, the same honesty, the same humor, and reflect pain and joy and everything in a way where we can take another step forward.”

–by Karen Kraco