Maggie Thompson is a textile artist and designer who has drawn inspiration from her Fond du Lac Ojibwe heritage and the broader Native American experience — but also from her own relationships and family history. And increasingly, she is discovering the meaningfulness of bringing her relationships and community directly into her artmaking process.

Thompson, who has exhibited with the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the McKnight Foundation and the Minnesota Historical Society is currently featured in “Sharing Honors and Burdens: Renwick Invitational 2023.” The show is hosted at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., the branch of the Smithsonian American Art Museum focused on contemporary craft and decorative art. This is the tenth Renwick Invitational and the first time that all the artists featured are Native Americans and Alaska Natives.

Alongside her fine arts practice, Thompson runs a knitwear business called Makwa Studio, operating in the Northrup King Building in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District.

The first of Thompson’s three pieces on exhibit, Body Bag, is a series of three body bags hand stitched with star quilts over the top. Within indigenous communities, “star quilts are often given away as gifts, and some tribes put them over a body when they’ve passed,” explained Thompson. The work references the collective loss and grief of the COVID pandemic, with the star quilts “paying homage to the indigenous communities that were impacted at higher rates.” But beyond the indigenous reference of the body bags, the piece is about the universal experience of grief and loss. “COVID impacted the whole world.”

As the deadline for the Renwick Invitational approached, that theme of collective experience took on new dimension for Thompson. “It started as a project that was solely myself; then I brought on a team of people to help,” she recalled. In the last week, Thompson put out a call to the community and on social media to help finish the intricate beadwork, quilting and hand stitching. “At first it was friends and family, but then random people just started showing up. There must have been at least 50 people. It turned into its own thing, which was beautiful because a lot of great conversations and connections were created.” Thompson said she is still processing how emotional that shared experience was. “It felt more appropriate,” she said, finishing the project with the community effort.

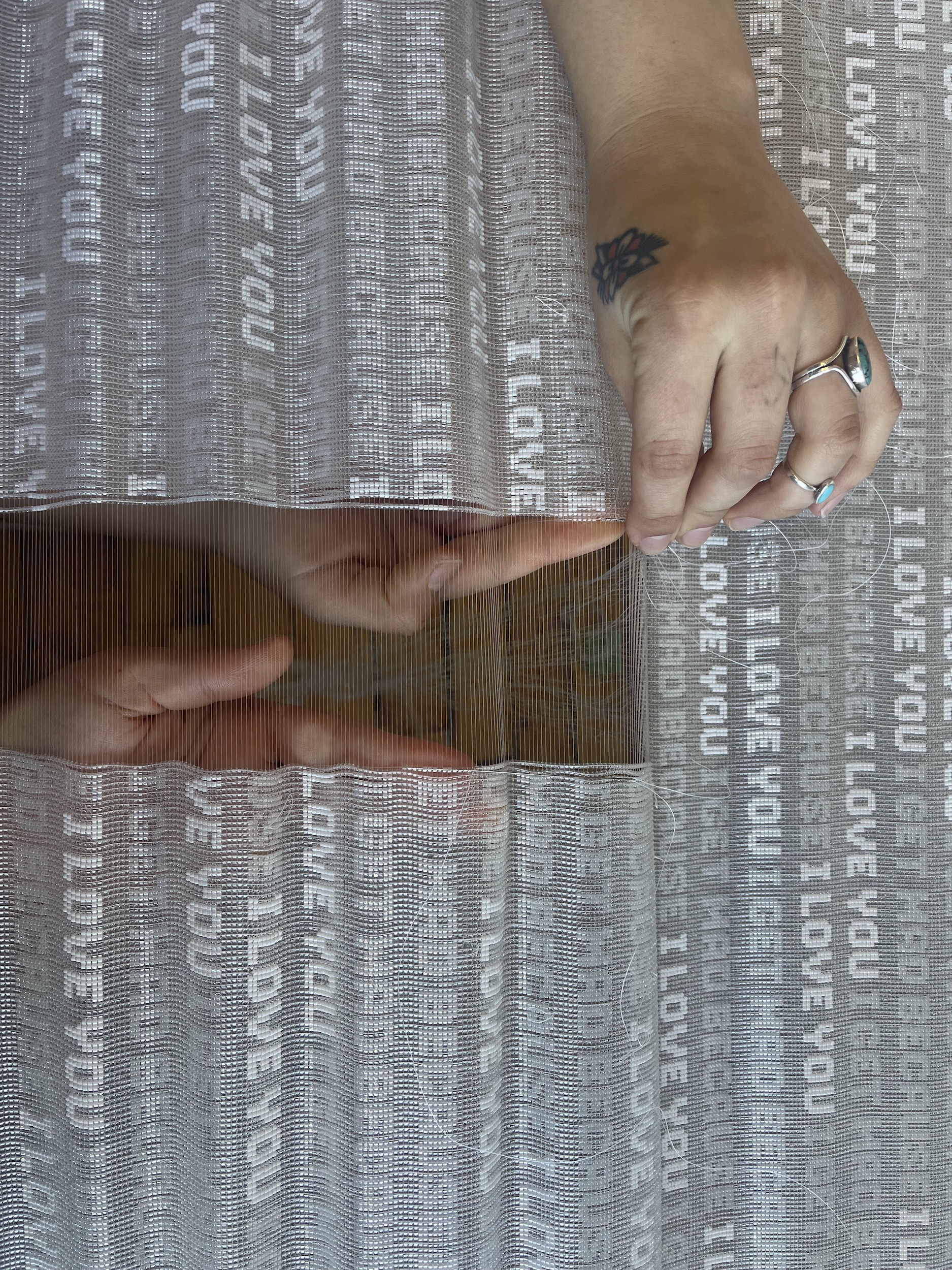

Two other pieces in the show touch on another widespread, but deeply personal theme: psychological abuse within relationships. In one, the words “I get mad because I love you” are repeatedly beaded across a giant 4’x6’ loom work. The different shades of clear and white beadwork make “I love you” stand out more legibly, emphasizing the difficulty of deciphering between action and words in situations of psychological abuse. The piece is edged with jingles that, for Thompson, reflect the process of healing from those experiences.

A second piece exploring similar themes places an emphasis on “paying attention to action and body within relationships,” Thompson explained. It is constructed from ropes that are tied in knots, then covered in different shades of stockings and tied with red ribbons. An accompanying quote — “A belly tied in knots with the red flags that you so delicately placed but insisted did not exist” — references “the importance of listening to your body in those situations.”

Thompson said she sees such themes as universal, but also seldom discussed in public. Psychological abuse, perhaps by its nature, is often experienced very privately. “It’s not easy to talk about.” In creating this work about something that is at once intimate and universal, Thompson has sought to create a point of connection for people who might not find it elsewhere. She said it’s been encouraging to see people from diverse backgrounds resonating with the work.

The sheer volume of foot traffic through the Renwick Gallery is significant to Thompson. “I think about how many people from all over the country and the world are coming into these institutions and getting a glimpse to better understand our culture.” The opportunity to show alongside the five other Native American artists is particularly meaningful as well. “All of the artists are talking about really important things from their unique perspectives.” On Sept. 7, Thompson will join fellow artist Erica Lord (Athabaskan/Iñupiat) and guest curator Lara Evans (Cherokee Nation) for a virtual conversation about cultural identity as it relates to their creative practice.

The experience of finishing the work for the Renwick Invitational so collaboratively has Thompson thinking in new ways about future work and collaboration at Makwa Studio. “I’d been working mostly by myself until last year, but since I’ve hired on more help, I’ve been figuring out what it means to mentor younger artists.” She said even though the work she offers is more production than design, they are learning traditional art forms. She said she is motivated to offer a safe space for artists who are trying to find their footing in the art world.

“We have a really good art community in Minnesota.” In creating the work for the Renwick Invitational, Thompson said the support from her local community made the show more meaningful than she expected. As she is processing the unexpected impact of total strangers walking in, some staying until 2 a.m. to help finish the work, she is imagining opportunities to open the studio doors for community learning and projects. “I felt the love from the local community,” she said — and now she wants to find ways to carry that love forward.

By Katherine Boyce