Howard Christopherson is busy inside his ICEBOX Gallery space preparing a show of fellow photographer Marc Norberg’s work. Christopherson is curating the exhibit with evident admiration for Norberg’s photography—but also the peculiar ache of knowing that Norberg himself may not recognize any of the images. Norberg is living in Saint Paul with moderate dementia, which has progressed enough that his mind is now opaque to his long-time friend.

Christopherson says the show is not a retrospective of Norberg’s work, in part because there simply isn’t enough space in his gallery to fully catalog Norberg’s prolific career. Rather, the exhibit is focused on Norberg’s body of innovative personal photography, work he created mostly out of the limelight. Call it an introspective, Christopherson urged.

Christopherson has been a mainstay in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District for decades; at 36 years, ICEBOX is the oldest fine art gallery in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District. Established in 1988 at its first location at 24th and Central Avenue, ICEBOX relocated to the 4th floor of the Northrup King Building in 2004. The upcoming show—“Inside Looking Out”—will be the 147th ICEBOX exhibit.

While Christopherson has exhibited Norberg’s work before, this current effort began almost two years ago when Norberg’s advocates hired Christopherson to sift through several storage lockers of his belongings in search of photos. It was a kind of treasure hunt. Amid the “mumbo jumbo” of CDs, props, studio equipment, furniture, and gardening rakes, “we would never know where there would be some photographic prints.” In the end, Christopherson and friends had unearthed 700 lbs. of negatives, just of Norberg’s commercial work.

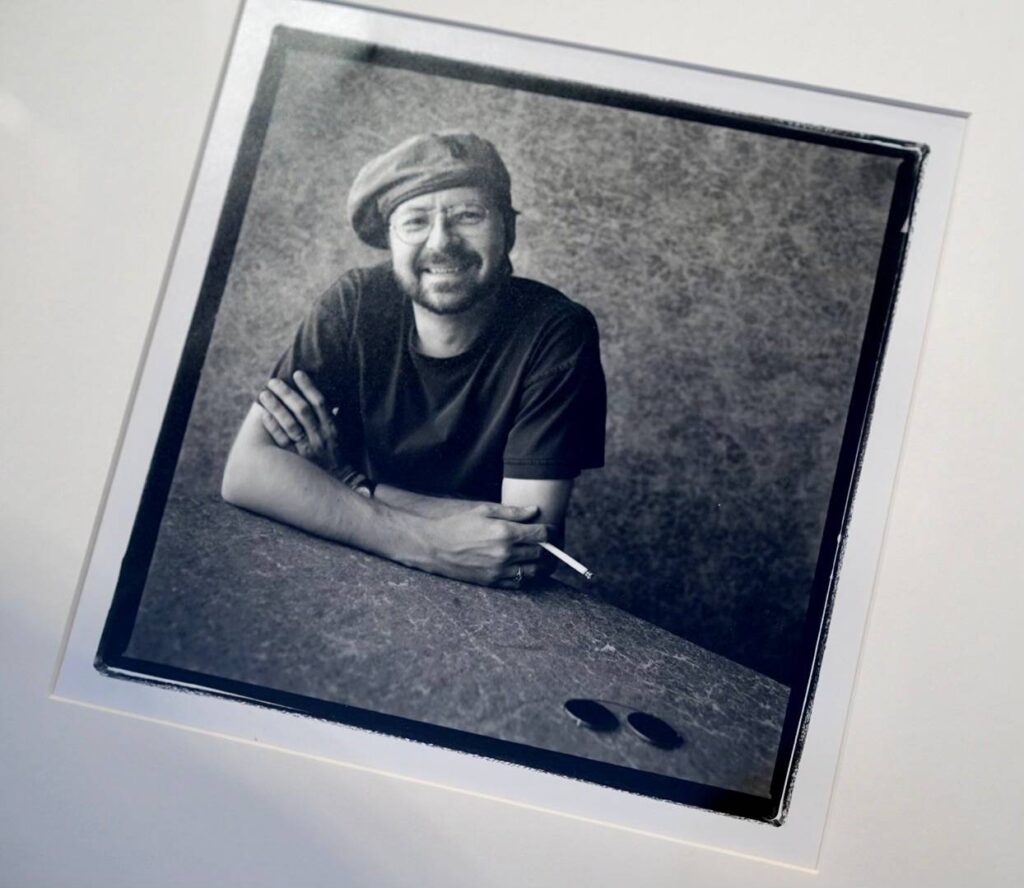

In the 1980s and ‘90s, Norberg was well known and highly sought-after as a commercial photographer in the Twin Cities, operating a beautiful studio above Nate’s in downtown Minneapolis and traveling internationally for work. He was known as a master of lighting. His portraits of corporate executives, famous scientists, celebrities, and Blues musicians won many commercial-art awards.

“Somewhere along the way, the Blues really affected him,” recalled Christopherson. There was “something about the organic realism of the blues” and “the realness of the spirit of it” that captured Norberg’s artistic attention. Norberg became friends with the owners of the local night clubs, including the Blues Saloon in Saint Paul, which allowed him to connect with the artists. A photo book of his Blues portraits—Black & White Blues—was published by Graphis, including portraits of John Lee Hooker, Etta James, Johnny Winter, and many more. Christopherson remembers him proudly saying that, of all the portraits B.B. King had of himself, he said Norberg’s was his favorite.

While Norberg’s commercial work brought huge success, Christopherson is focusing this show on those works that, in his opinion, crossed over into the realm of fine art. “He was very prolific. He saw art everywhere he looked.” Norberg could make a great photo of dust in a corner or cigarettes in an ashtray. And he was constantly experimenting; when he was commissioned to photograph scientists, he shot them through glass beakers, their faces distorted by the glass. He set up elaborate photoshoots, then stepped back and photographed the set itself. To Norberg’s eye, the umbrellas and flash equipment made their own fascinating scene. “People hired him because of his imagination. He saw the artistic-ness of all this stuff.”

There was something heartbreakingly prescient about Norberg’s attention to the objects of our human and artistic lives. The storage lockers full of negatives, the tubs full of journals, the photographs of whatever was in his pockets—these are what his loved ones rely on now. Christopherson dates the end of Norberg’s commercial career sometime around 2006, which he described as a kind of “perfect storm” in Norberg’s life. The recent death of his sister, who had Alzheimer’s, had a profound effect on him; Norberg’s studio managers were moving on; and sometime around then, his dementia progressed.

“It’s hard to remember that he’s still here, living in Saint Paul,” Christopherson said. It’s been a long time since he heard Norberg speak. But he said he could still get him to laugh. “Our minds are amazing things. They go from the most amazing brain that works in such a genius kind of way to just…a box of stuff.” It is as if “Inside Looking Out” is Christopherson’s way to keep on imagining what is inside Norberg’s brilliant mind.

The show will have no didactics. Christopherson doesn’t have information for most of the work, no dates, no titles—and no Norberg to fill in the context. He chuckled that it means Norberg isn’t there to tell him he’s doing it all wrong. But reading between the lines of Howard’s devotion to Norberg’s work, it’s clear he wishes he were.

Christopherson came across a haunting self-portrait that embodies the show. In the image’s uncanny double exposure, Marc himself has all but disappeared. The sharpest focus rests on his torn jeans and wrinkled shirt, lying emptied on the floor. “That’s sort of like life, that we all fade away. And what did we leave behind?” In Norberg’s case, a wondrous collection of his works of art is in good hands. More about Norberg here: https://www.iceboxminnesota.com/norberg/norberg.html

Article by: Katherine Boyce